Adam Rivett: I wanted to start with a phrase you use in words accompanying your new collection — “Increasingly, I want to abandon what I’ve gained and be done with compromise. The desire is always to see clearer, to shed impediments and falsities.” It’s an interesting idea I see many artists wrestle with — trying to find a new voice and get out of old habits. I’ve always found it easier to conceptualise when I think about a musician changing their sound or a writer trying to alter their prose. How do you think this desire to change and “unlearn” manifests in a photograph?

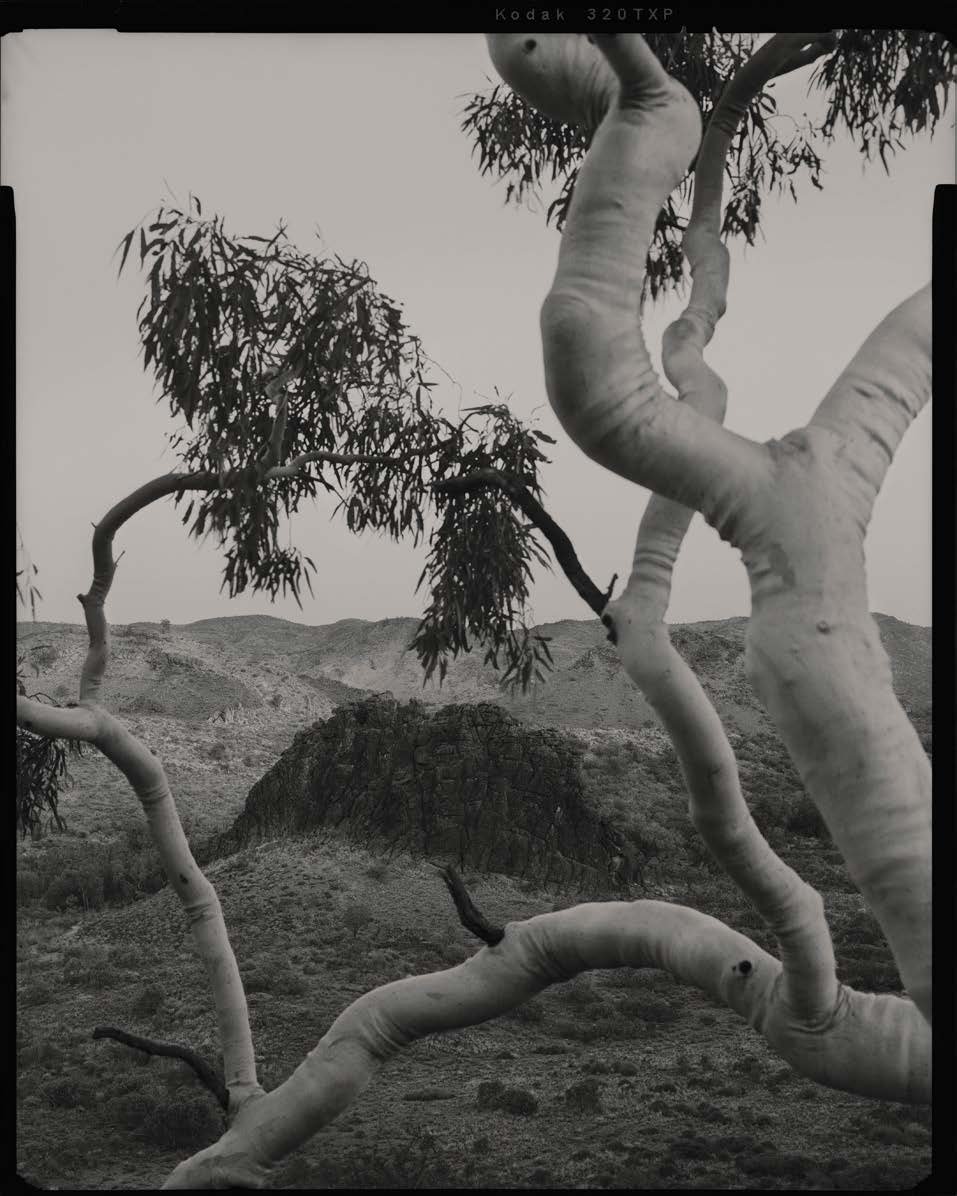

Yarretyeke on Arrernte Country [Redbank Gorge, West Macdonnell Ranges, NT], 2023 From a portrait of [country]

Ingvar Kenne: I’m still trying to figure that out. This project, which is three years in the making, still feels like it’s in its infancy. And I think of it more as finding my first voice than finding a new one.

Lately, it has become important to revisit memories of those first moments as a young teenager, developing black-and-white images of a duck I photographed during a trip to visit my grandmother in Northern Germany. My dad helped me build a makeshift darkroom in the basement sauna at home. There was something so new and powerful in that room without light. I wanted to get back to that feeling and retrace those tentative steps into a world I found instantly magical. Albert Camus once said: 'A man's work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.'

The Duck Image, 1979.

And now, forty-five years later, I’ve decided to set strict parameters — using the same film and chemical processes as back then. But, even more important than that, I want to try to find images to help me rediscover those early sentiments. My belief was that I needed to go back to the land, to unspoilt country. Through lifelong exposure to so-called normal life, I needed to clean my polluted mind. I wanted to experience and find places that were not altered by man. Non-colonial places that I felt still held magic.

AR: I guess this question tags onto the last one — it’s about seeing, too. When I look at your ongoing CITIZEN series, I see you trying to bend and undo many of the cliches and received notions of portrait photography. Likewise, with these landscapes, do you think there are habits you can fall into when shooting the land?

IK: Absolutely. Though I do love habits and works that echo each other. I strive to create a series of images with those resonances. I find repetition or common denominators incredibly powerful in any artist’s work. They give the viewer an opportunity to build their own narratives within a contained visual language. If an artist is too broad and always tries to reinvent their approach, I stop comprehending and lose interest. Hence, CITIZEN has been going on for thirty years now. Its inception was a portrait that completely consumed me once I saw the film. After that, it became the drive to find another portrait, and yet another, that had the hallmarks of the first one. Most important to the work was maintaining my own path and preserving a certain mindset — to try to stay narrow yet invite change, all the while having one singular box of established ways as a part of me and my practice.

Cormac and Callum Kenne, My Children, Sydney, Australia 2009. From Citizen - since 1997

Angus Young, Musician, Sydney, Australia 2003. From Citizen - since 1997

It doesn’t matter if they’re a priest or a prostitute, a celebrated actor or a cleaner down the local pub — or indeed my own family. They are all CITIZENs. I always turn up with the same approach — stay curious and summon instinct, yet give myself as few options as possible. There are a lot of no-gos I give myself, but within what I say is allowed, I give myself complete freedom to express and embrace chance.

As for rules and habits, with these new landscapes, I only have one camera, two almost identical lenses, and a backpack full of film. I am not allowed to photograph landscape format, only verticals. I can’t pick a wider lens. The camera needs to be on a tripod. I only take two shots of a scene. There are more rules, but I’ll spare you the rest. The possibly contradictory thing is that I find rules actually free me up. With options gone, the clutter in my head disappears. My eyes adjust to this one set of parameters and start seeing the world differently.

Anonymous Couple, Holiday Makers, Chu Da, Vietnam, 2015. From Citizen - since 1997

Yvonne Margula, Elder Mirarr People, Kakadu NP, Australia, 1998. From Citizen - since 1997

I have definitely found where I want to be visually with this work, but plates that are now part of the project might be nudged out and disappear once I tell myself the project is complete. Something similar might have come along, and if it holds more power for me, that’s the one I keep. I’m open for the work to evolve until it tells me otherwise.

Before setting out on a journey in my fully loaded Landcruiser, often for months on end, I do as little research as possible. No preconceived notion — I want to be receptive to what happens — meeting people, hearing stories, having weather disruptions. All of it. When, in 2020, I spent two months in the Central desert area of SA and NT, all I knew was that I wanted to revisit Uluru and Kata Tjuta 37 years after my first and only visit. Instead of a three-day drive, it took me ten to get there. The entire trip continued in that fashion, deciding in the moment what was next.

AR: Is it a challenge to find the right angle — I’m quite interested in how something so infinite and graspable forces you to choose how to approach it. Photography is about scale and choice, but it’s easier to corral a human subject or even a particular moment like a crowd shot or a vista. But the land is vast and offers you a million potential angles. What’s the process of finding the “right” one, if you want to call it that. And how much trial and error were involved in this process?

Karlu Karlu on Warumungu, Kaytetye, Alyawarr and Warlpiri Country [Devils Marbles, NT], 2023. From a portrait of [country]

Didthul on Yuin Country [Pigeon House Mountain, Morton NP, NSW], 2023-2024. From a portrait of [country]

IK: Once I find myself where things start to fall in line, I get quite methodical. It involves lots of walking and scouting the place, often several times, before I slowly identify what’s beckoning me back. The camera is on my back at all times, so if it all falls into place at that very moment, I can take a photograph. Sometimes, I stay put for the rest of the day, waiting for changes to light and clouds. That can lead to nothing as often as it does to a photograph. Some places I return to three or four times. Each trip could involve a ten-kilometre walk.

Again, the rules are often my salvation. Standing in front of Kata Tjuta, in spots allowed and tightly regulated for very good reasons, I found that I could not fit in what I wanted to capture. Out of that was born my first diptych using two 4x5 plates side by side to make up the image. That led to a triptych a few weeks later. Now, they are part of my regular approach — used as a tool if the landscape asks it of me.

AR: How did you find the particular locations we see in the series in its current format? Was finding them a challenge in and of itself before you even considered them aesthetically?

IK: All of them required various challenges. They all emerge from journeys that require me to leave paid work, to leave home and studio behind, often for long periods of time. Invariably, these places are hard to find, far from towns and cities. There are miles of long, beautiful, lonely roads to travel. At times, I just end up driving into a space of such magic I need to stop and camp for the night until I have figured out why I had to stop.

Then there’s the walking. I hadn’t done any research for my month-long Tasmanian trip. I had some awareness of a few places, having worked there before. Having driven off the Spirit of Tasmania, I thought I was going to the northwest corner, but instead, I ended up walking high up that afternoon into the Cradle Mountains. The day after, I did a Google search of Tasmania’s favourite tracks, and The Western Arthurs Traverse repeatedly came up as number one. I decided to go. Little did I know it’s considered one of the physically toughest in Australia. My camera gear, including film, cassettes, film loading tent and tripod, came in at 15 kilos. Add to that my tent, food, fuel and clothing, and I was topping out beyond 30. I was setting out alone in constant rain and kilometres of muddy, swampy trails pushing through gnarly vegetation while also ascending vertically, probably up to a kilometre a day. I spent a week there and walked away with three works — I see that as a very successful week.

Ingvar Kenne & Joseph Williams, Exhibition view at day01. gallery 2024

AR: You touch on our Indigenous culture and its connection to land in that same artist statement I quoted earlier: “As places still echoing with their pre-colonial life, I had to see what you’ll in turn find in these photos without ego – a kind of pictorial abnegation.” How conscious are you of this when you’re on location shooting?

IK: My whole artistic arc has been to take a path into the unknown, to explore and be curious about “the other”. Almost none of my work derives from where I come from. I grew up comfortable in one of the most liveable places in the world, and I could not wait to leave. I have spent a lifetime on the road, travelling to seventy-odd countries. I’m inevitably drawn to indigenous ways of relating to one’s surroundings, no matter which part of the world I’m in. This travelling has enriched me in expected ways, but it also developed a strong sense of not belonging to any particular thing. There has never been any other way for me to make sense of my own position than to be curious about what I don’t know. That curiosity eliminates my fears and hesitations, the sort of thing that leads you to suspect that “other” as a threat.

A global motorcycle journey that began in 1994 was the catalyst for me to move to Australia. My first son, Callum, was born in 1999, followed not long after by my second, Cormac. Those two events alone anchored me firmly in this country. This is the land of my children, and they carry their own line of sight — and they walk the country I also call home. For me, particularly while on untouched country, it is impossible to ignore 60,000 years of continuous living, in lockstep with the land. And yet, the opposite is also true. All the scars, the disruption, the dispossession, the repeated and now complete colonial take-over — that’s also part of the land itself. The paddocks, the towns and cities, the underground, the waterways and the air — it’s all affected.

What I mean by a pictorial abnegation is that I have spent a whole lifetime in absolute comfort and relative modern luxury and white privilege, surrounded by the values and aspirations that come with that. It’s also a lifestyle hedged within a particular visual language. When walking on this country, looking for these rare places where the earth is humming, I want to try and rid myself of what I was fed and taught. Because none of those comforts, extravagant number of possessions, nor Christian colonial values means shit, especially when you sit on a piece of magical dirt watching the sun set or rise, and you start to grasp your surroundings with complete acceptance.

Ingvar Kenne on Darkinjung country, 2020.

Corroboree Rock, Arrernte Country [East Macdonnell Ranges, NT], 2023. From a portrait of [country]

AR: I wanted to ask how you felt this ongoing photographic project connected to your wonderful feature film — that word again — The Land. I was lucky enough to see it last year, and in the film, there’s a similar suggestiveness and historical allusiveness in the use of landscape. Does it feel like a natural overlap between projects or that they’re even in communication with each other?

IK: Most of that film is set in old-growth forest surrounded by Wollemi NP — where I have 75 acres. A place I know intimately, having spent twenty years exploring with my family — building a couple of small shacks for shelter. So, the landscape, the land, is very much a main character in that film, with a strong nod to times past. The film’s title simply came from how we used to refer to it as a family — we were always heading to The Land.

The two projects are connected in some ways, for sure, though they never set out to be. If you stay honest with yourself, no matter your artistic output, thematic connections across different mediums will come from the same author.

Film still from The Land, 2021 Watch trailer here

AR: Is there any work that’s resonating for you at the moment? And what I’m thinking here isn’t simply a photo/film you liked, but any artistic work that clicked for you, anything that seemed, in a roundabout way, as an achieved ideal of what you were after in rethinking your artistic practice? I call them “exemplary works” — works that point the way forward, even if it’s just for you. Does anything like that ring a bell, or has anything else resonated with you like that of late?

IK: Many works of art, music and film have had an impact on me, but I will only tell you what first comes to mind. In this show at day01 Gallery in Sydney, I share the wall with Tennant Creek Brio artist Joseph Williams. Eloise Hastings, the director of the gallery, told me a few months back she had these two traditional stone axes she bought for herself that she liked to put on the wall next to my photographic work as a counterpoint, the work having been made not far from where one of my images were taken. She told me about Joseph and his practice, and it dawned on me that we had met before. While on the very journey during which I was taking many of the images in the show, I went to Alice Springs Art Gallery. In the large room was a lone man in front of some work. We started a conversation, and it turned out to be Joseph, who had travelled all the way from Tennant Creek for the day to look at his own work hanging. I took his portrait and sent it to him as a memento, and we then parted ways.

AR: Feels almost predestined.

IK: Possibly. I think staying curious helped us meet. I’m really excited to share the space with the power and brilliance of Joseph’s traditional stone axes and paintings. He uses old mining core samples to split up the cylinder to make the axe head, and he paints over old mining prospecting maps with Waranmungu stories. Meeting Joseph has been a revelation, and the reflection his work and words cast on my own is truly meaningful to me.

Joseph Williams, Kooloongka kiri, 2021. Ore body core sample, snappy gum, yakala

Ingvar Kenne & Joseph Williams. Exhibition view at day01. gallery 2024

AR: I’d like to return to the opening theme around rethinking or “unlearning” photographic ideas. Going forward, whether it’s an extension of this ongoing project or something else, where do you think your current ideas about practice and seeing will take you? Do you think there’s a subject or an approach still waiting as you move into this new phase of work?

IK: I feel so deeply involved in this project and my other ongoing ones that my head is full. I can’t think beyond it. I do have a wish, though, to go back to the beginning of CITIZEN, to that around-the-world motorcycle journey in 1994. I’d like to ship my old motorbike to Cape Town in South Africa, head north, and see how far I get. I’ve always wanted to go to Ethiopia, so that will probably be my direction. Be away for a year, meet some new amazing people and take each day for what it is. I would love that. But it has to be put off for a while since it looks like a portrait of [country] will take precedence for the next couple of years.

If the opportunity arose and I found an amazing script, I would love to be involved in yet another feature film. But it has to be the right one — three to five years of your life is way too precious to throw at something you don’t fully believe in.

All works © Ingvar Kenne (unless otherwise stated)

Explore Pool | Explore Ike