Fragments of Forgotten History — Conversation with Nicholas Hubicki & Adam Rivett

By Adam RivettLast July, I stood before images that have remained hard to forget. The show was Half the World Must Be Buried Alive, and its creator was Nicholas Hubicki. A collection of stark power and stern reflection, it collects, rediscovers and reimagines material regarding Victoria’s now-closed mental health institutions, J. Ward and Aradale. The show forms a fragmentary portrait from a vast collective amnesia via patient letters, instruments, admission photographs, psychopharmacological molecular models, and the spaces and environs of the institutions themselves. The exhibition was made possible with the support of The Pool Grant, an initiative fully funded by The Pool Collective. Launched in 2010, the grant was created to support the development of emerging talent within Australia and New Zealand. Since then, it has funded ten individual artists and the first joint project in 2018/19. Throughout each project, Pool’s artists have acted as mentors to each year’s recipient, assisting with their process and guiding them through the rigours of creating a solo body of work fit for a gallery space. A year later, on the verge of the newest Pool Grant exhibition, I sat down with Nicholas to discuss his show and the lingering traces still discoverable in his indelible imagery.

Adam: Before we talk about the Pool Grant and your collection Half the World Must Be Buried Alive, can I ask you about your earliest photographic efforts and what directed you towards the medium?

Nicholas: My earliest childhood “photographic efforts”, such as they were, were rather forgettable. My father’s camera, a Nikon F2, was something I regarded with a certain awe and danger. It was a beautiful and mysterious object, and my father was very particular in its use, so using it meant accepting a certain amount of anxiety. I was also fond of my mother’s automatic Polaroid camera, which at the time had the excitement of the instantaneous. I was intrigued by how ghostly I often found the images. It took me a long time to understand that a camera isn’t simply a reproductive device.

A: To the exhibition in question – though you’d exhibited and published your work before, how did receiving the Pool Grant change your approach, and how did the specifics of the grant help your work? Was there anything new involved with Pool or other creative people as part of that experience that changed or developed you as an artist?

N: One of the most important aspects of the Pool Grant for me was the regular review sessions, which helped to structure the work and, more importantly, helped me gauge where the work was at from an external perspective; it’s easy to be solipsistic. My general working method is highly insular and hermetic, so to be challenged at certain points was a fresh injection of oxygen. The level of support was both incredibly motivating, and - given that it was a time of major personal upheaval for me - compassionate.

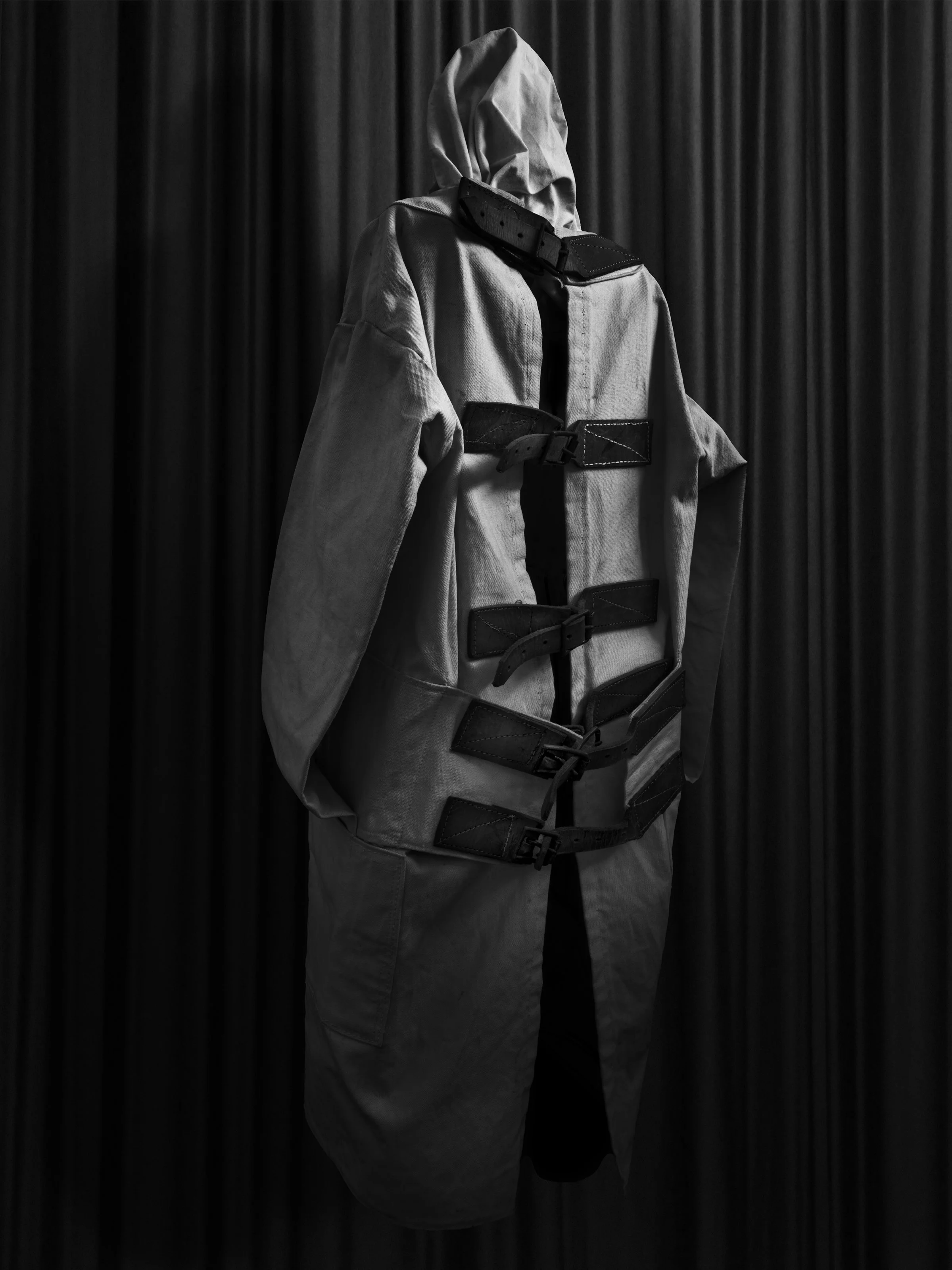

A: Many of the most striking images in Half The World involve the straitjacket used at J Ward and Aradale. Visually, they’re overwhelming – they’d almost be perfect for a death metal album cover. There’s something incredibly foreboding about them, dark and menacing but also lustrous, resonant. Almost beautiful. But at the same time, nothing about what they did is beautiful in the slightest. How to split that difference between something which is striking or aesthetic resonant and something which carries a haunted, negative connotation?

N: It’s strange –yet comforting – you say that. In many respects, the jackets were the ‘fulcrum’ of the show: they were printed almost at a 1:1 scale in an attempt for the viewer to feel themselves in them, to feel or suggest the horror of being forced to wear such constructions. The correspondence of some of the inpatients suggests the great disbelief in being ‘incarcerated’ there in the first place, let alone being restrained in such a manner. The ethical problem of ‘aestheticising’ - or representing - such objects is one that I haven’t quite fully resolved, in the same way that I haven’t processed the visual beauty of 9-11 against the seismic horror of its mortal impact. It’s a condition central to photography and one that I am both uneasy with and yet – in this case – an abettor.

A: I’m interested in the way the exhibition splits the difference between archival work like letters and mugshots and your own “present-day” shots. Obviously, there’s a strong sense of redress and correction in the show – an accounting for the sins of the past that still linger in the present. Is it hard to strike that balance when you’re playing creator and curator simultaneously?

N: As much as I’d like to have been able to “redress” this history, the ambition was more to suggest a kind of trajectory. The archival sources - rather, more access to them - was heavily proscribed, hence there is a gap, like a psychic ‘patch’, in the “curation” of this trajectory. The molecular models I built - and then photographed - of various historical psychotropics forged a kind of ‘more complete’ historical continuum yet are merely diagrammatic abstractions of their intents. The exhibition attempted to work from first-person accounts (in the form of letters) and diagrammatic abstraction to the documentation of the (present-day) environs and its former ‘machinery’, yet also suggest - via cloudscapes (i.e. analogy) - certain psychological disturbances.

A: The patient testimony sampled through letters in the show is very moving, likewise those images of isolated shock therapy and submersion tanks. When I walked around the room the night I saw the show; I could palpably feel the cruel history of those objects. How do you approach the still-life aesthetic regarding objects with such a negative aura around them?

N: It was a difficult problem that I - and Pool - returned to frequently. There were times reading the letters at PROV (Public Records Office of Victoria) that left me deeply shaken. The paste-in sheet of categories of disorders in one of the patient casebooks - depicting an utterly alien contemporary understanding in many cases - led me to reflect on the objects as dispassionately as I could, mirroring the clinical taxonomies, yet also maintain the ‘curiosity’ in what these objects were, what their function was. I’m often intrigued by the visual ambiguity of some of these objects while knowing their function, which is often still an ethical struggle for me.

A: Following on from that, I wanted to ask about history and advocacy. The show is an accounting and reckoning with a dark period of history, but you mention in the text written for the show. I quote: “Half the World Must Be Buried Alive does not seek to systemise or catalogue, but to depict a certain pre-history whose mechanisms and procedures may now seem - at first glance - obsolete, yet equally informed contemporary mental health practices.” So there’s a present-day concern there too, with an eye towards social justice. We can’t simply file this stuff away as a “know nothing past”. How do you feel your work and photography, in general, might engage with progressivism and the consideration of contemporary issues?

N: I think very much of Michel Foucault and his books, particularly Discipline and Punish and A History of Sexuality. They’re archaeologies that describe the roots or trajectories of certain practices that are still present. A present can only exist with a past, and that past - like any past - informs its present and future. My show attempted to sketch - via several photographic modes - a fragmentary ‘portrait’ of institutional mental health care in the twentieth century. Photography is only one tool available, as powerful as it may be, yet it’s also heavily reliant on allied forms, especially writing, and neither can act politically without action.

A: Finally, that tiresome age-old question, what’s next? I’m particularly fond of your new series, Chimera.

N: Thank you. It seems that artificial constraints and behaviour modifications have also informed that work. Hopefully, the sketchy new works are far more…unbridled.